Theory Chapter 3 Analogy

Analogy(adapted from Gentner and Markman)

Our structure-mapping abilities constitute a rather remarkable talent. In creative thinking, analogies serve to highlight important commonalities, to project inferences, and to suggest new ways to represent the domains. Yet, it would be wrong to think of analogy as esoteric, the property of geniuses.

Dedre Gentner and Arthur B. Markman

Analogy and similarity are central in cognitive processing. We store experiences in categories largely on the basis of their similarity to a category representation or to stored exemplars. New problems are solved using procedures taken from prior similar problems.

First, analogy is a device for conveying that two situations or domains share relational structure despite arbitrary degrees of difference in the objects that make up the domains. Common relations are essential to analogy; common objects are not. This promoting of relations over objects makes analogy a useful cognitive device, for physical objects are normally highly salient in human processing - easy to focus on, recognize, encode, retrieve, and so on.

A new and creative solution usually results from the fusion of pieces of knowledge that have not been connected before.

Geschka and Reibnitz

The process of comparison both in analogy and in similarity - operates so as to favour interconnected systems of relations and their arguments. As the above discussion shows, to capture the process of analogy, we must make assumptions not only about the processes of comparison, but about the nature of typical conceptual cognitive representations and how representations and processes interact. In particular, we must have a representational system that is sufficiently explicit about relational structure to express the causal dependencies that match across the domains. We need a representational scheme capable of expressing not only objects but also the relationships and bindings that hold between them, including higher Structure Mapping in Analogy and Similarity order relations such as causal relations.

There is, in general, an indefinite number of possible relations that an analogy could pick out, and most of these are ignored.

The defining characteristic of analogy is that it involves an alignment of relational structure. There are three psychological constraints on this alignment. First, the alignment must be structurally consistent In other words; it must observe parallel connectivity and one-to-one correspondence. Parallel connectivity requires that matching relations must have matching arguments, and one-to-one correspondence limits any element in one representation to at most one matching element in the other representation structure. This also shows a second characteristic of analogy, namely, relational focus: As discussed above, analogies must involve common relations but need not involve common object descriptions. The final characteristic of analogy is systematicity: Analogies tend to match connected systems of relations. A matching set of relations interconnected by higher order constraining relations makes a better analogical match than an equal number of matching relations that are unconnected to each other. The systematicity principle captures a tacit preference for coherence and causal predictive power in analogical processing. We are not much interested in analogies that capture a series of coincidences, even if there are a great many of them.

In a study, people who were given analogous stories judged that corresponding sentences were more important when the corresponding sentence pairs were matching than when they were not. Alignable differences can be contrasted with nonalignable differences, which are aspects of one situation that have no correspondence at all in the other situation. This means that people should find it easier to list differences for pairs of similar items than for pairs of dissimilar items, because high-similarity pairs have many commonalties and, hence, many alignable differences. Such a prediction runs against the common-sense view - and the most natural prediction of feature - intersection models - that it should be easier to list differences the more dissimilar the two items are. In a study by Gentner and Markman (1994), participants were given a page containing 40 word pairs, half similar and half dissimilar. The results provided strong evidence for the alignability predictions: Participants listed many more differences for similar pairs than for dissimilar pairs. It seems it is when a pair of items is similar that their differences are likely to be important.

Analogical Inference is another effect of use in delivering Innovation. Studies (Clement and Gentner 1991) show analogies lead to new inferences. In analogy, when there is a match between a base and target domain, matching facts about are accepted as candidate inferences. Mapping allows people to predict new information from old and will allow us to use analogy to suggest innovation options by using an existing product as a base domain.

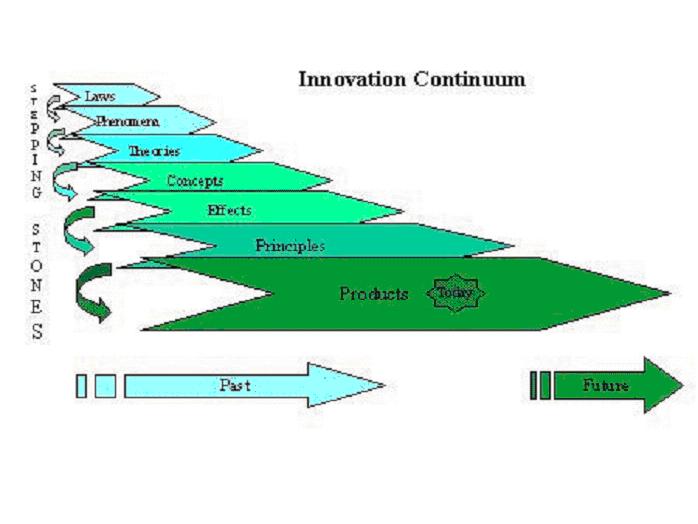

Selecting existing product as a base domain has other benefits. According to structure-mapping theory, inferences are projected from the base to the target. Thus, having the more systematic and coherent item as the base maximises the amount of information that can be mapped from base to target. Consistent with this claim, Bowdle and Gentner found that when participants were given pairs of passages varying in their causal coherence, they (a) consistently preferred comparisons in which the more coherent passage was the base and the less coherent passage was the target, (b) generated more inferences from the more coherent passage to the less coherent one, and (c) rated comparisons with more coherent bases as more informative than the reverse comparisons. The inherent coherence of an existing product in its tangible and viable setting, makes it a superior option to a great leap forward from a law or technological advance.

It is possible that conventional analogies have their metaphoric meanings stored lexically, making it unnecessary to carry out a mental domain mapping. This could be the reason that it is easier to extend an existing domain mapping than to initiate a new one. For example, when electric current is described throughout a passage using the extended analogy of water flow.

Innovators are called on to map information from one situation to another and they must decide which aspects of their prior knowledge apply to the new situation. Schumacher and Gentner (1988) found the speed of learning was affected both by transparency (i.e. resemblances between structurally corresponding elements) and by systematicity (i.e. when they had learned a causal explanation for the procedures). Having a strong causal model can enable innovation even when the objects mismatch perceptually. Both transparency and systematicity are facilitated by drawing analogy between products.

Several findings suggest that similarity-based retrieval from long-term memory is based on overall similarity, with surface similarity heavily weighted. a parallel disassociation has been found in problem-solving transfer: Retrieval likelihood is sensitive to surface similarity, whereas likelihood of successful problem solving is sensitive to structural similarity. This suggests that different kinds of similarity have different psychological roles in transfer. For instance studies of relational comparisons suggest that when participants are required to respond quickly, they base their sense of similarity on local matches rather than on relational matches. At longer response deadlines, this pattern is reversed.

Structural alignment influences which features to pay attention to in choice options. Research suggests that alignable differences are given more weight in choice situations than are nonalignable differences.

In order to find concepts for transforming products the prime method available is to draw analogy with concepts used by other products. Analogy is particularly well suited because of the way the mind builds ideas from images and memory fragments.

Analogy also has an important place in engineering and invention. Velcro, as no doubt everyone knows, was developed by analogy to the grasping properties of the common burr.

Robert Root-Bernstein and Michele Root-Bernstein

Analogy is the quality or state of being alike or: affinity, alikeness, comparison, correspondence, likeness, parallelism, resemblance, similarity, similitude, uniformity, uniformness. Analogies can be used to group analogous relationships into five categories: descriptive, comparative, categorical, serial, and causal.

In our example, we might draw the analogy between the Dustpan and a rotary street sweeper and consider contra-rotating brushes on the brush handle that sweep together as the brush is pulled. The alternative conceptual forms of the product can be mapped using Innovation Ballistics and cued straight into our mental model for evaluation.

Analogy Cuing

"What we have learned over the years is that what you get out of memory depends on how you cue memory. If you have the perfect cue, you can remember things that you had no idea were floating around in your head,"

Kenneth Norman, professor of Psychology at Princeton University

"When you try to remember something that happened in the past, what you do is try to reinstate your mental context from that event," said Norman. "If you can get yourself into the mindset that you were in during the event you're trying to remember.

In an experiment, participants studied a total of 90 images in three categories -- celebrity faces, famous locations and common objects -- and then attempted to recall the images. Norman and his colleagues used Princeton's functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner to capture the participants' brain activity patterns as they studied the images. They then trained a computer program to distinguish between the patterns of brain activity associated with studying faces, locations or objects.

The computer program was used to track participants' brain activity as they recalled the images to see how well it matched the patterns associated with the initial viewing of the images. The researchers found that patterns of brain activity for specific categories, such as faces, started to emerge approximately five seconds before subjects recalled items from that category -- suggesting that participants were bringing to mind the general properties of the images in order to cue for specific details.

Analogy is about finding similarities, categorizing, making comparisons and cuing memories.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home